She repeatedly described her characters as women with blue eyes, fair hair, and skin as white as ''pure'' or ''driven'' snow. Her books ''Four Girls at Cottage City'' and ''Megda'' follow a group of adolescent female friends in eastern Massachusetts from childhood to marriage, with no mention of the difficulties facing black women. In fact, in her complete works, there are only brief references to "colored" characters, usually servants.

She repeatedly described her characters as women with blue eyes, fair hair, and skin as white as ''pure'' or ''driven'' snow. Her books ''Four Girls at Cottage City'' and ''Megda'' follow a group of adolescent female friends in eastern Massachusetts from childhood to marriage, with no mention of the difficulties facing black women. In fact, in her complete works, there are only brief references to "colored" characters, usually servants.

So how did Emma Dunham Kelley-Hawkins become cited as one of the leading black writers of the 1890s by scholars of African-American studies, even inspiring, according to editor Henry Louis Gates Jr., the Oxford University Press's 40-volume Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers?

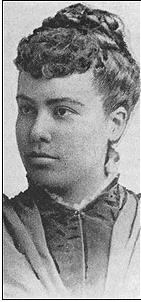

It apparently started with a misinterpreted photograph and was later compounded by torturous scholarly arguments such as the one that her characters would have been understood as ''white mulattos'' by readers in the late 1800s, or that her works were meant to represent a color-blind utopian future. Holly Jackson presents the story of how a woman thought to be a pioneer of African-American women's literature turns out to be a case of mistaken identity.

What fascinates me about this article is the a priori thinking demonstrated by the critics studying Kelley-Hawkins. Apparently because she has (arguably) African-American features in the photograph published in her novel, "Megda", critics claimed that she was clearly trying to identify herself as a black writer. And, if she were a black writer, then her work has to be African-American, even though her characters and subject matter had nothing to do with racial concerns of the 1890s.

Henry Louis Gates Jr. says he does not know how Kelley-Hawkins came to be

identified as African American. ''I'm intrigued by the idea, however, that so

many scholars have concluded that this woman was black, and it certainly will be

interesting for us to figure out why,'' he said in a telephone

interview.

No comments:

Post a Comment